On February 4th, 1983, a movie premiered that, although dismissed by critics and audiences alike on its release, has emerged as one of the most prophetic films of all time: David Cronenberg’s Videodrome. Marketed as a totally tubular, gnarly, new wave sci-fi flick that will totally gag you with a spoon, Videodrome’s advertising focused on the then queen of punk, Blondie’s Deborah Harry in her first movie role. Viewers expecting to be entertained with the same kind of MTV-style hijinks as evidenced in Blondie’s music videos for “Rapture” or “Heart of Glass,” would be sorely mistaken.

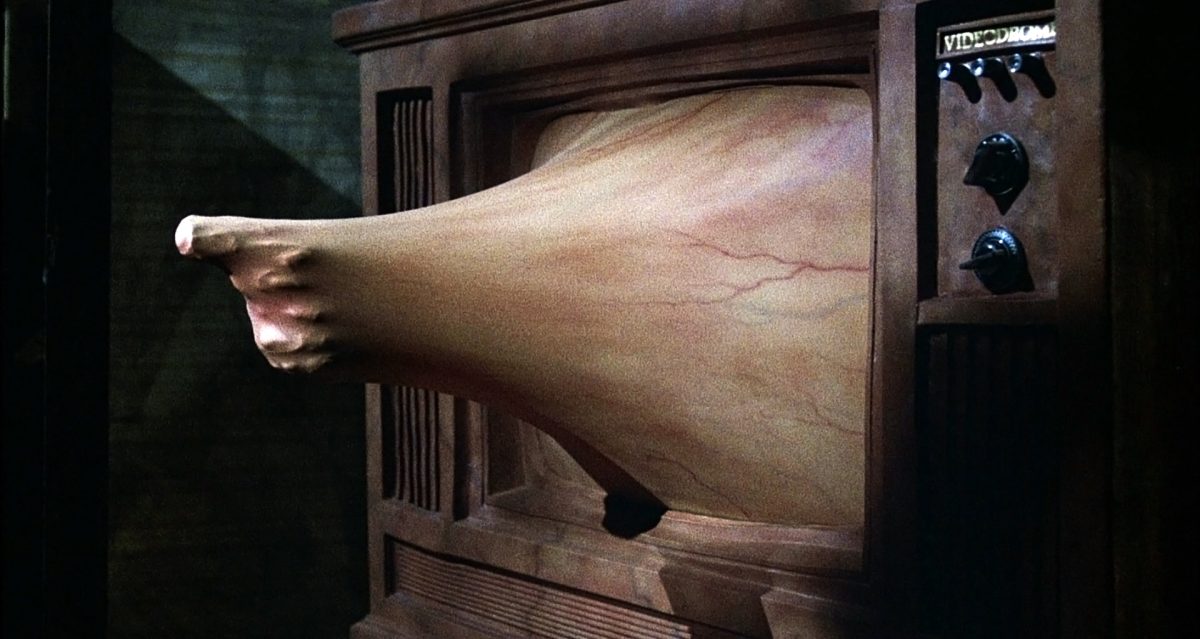

Videodrome focuses on Max Renn (played by James Woods, exhibiting his patented jittery nervous intensity), the owner of a small independent TV station CIVIC-TV who is constantly on the lookout for salacious and aberrant shows to keep his viewers watching and the advertising dollars rolling in. Searching the airwaves with his illegal satellite dish, he discovers a program called Videodrome, which appears to be real life torture and murder. The signal cuts in and out, and the images are hazy and blurred, but Renn is convinced that Videodrome is not only authentic but also the future of television. In his quest to uncover the origins of Videodrome, Max becomes caught up in a conspiracy to use the Videodrome signal to control the minds of its viewers and to destroy those who are deemed deviant because of their interest in extreme depictions of sex and violence.

Prior to his directing Videodrome, David Cronenberg had made several independent films and the success of Shivers, Rabid, Scanners, and The Brood, caught the attention of major movie studio Universal Pictures. Videodrome was Cronenberg’s first big studio film, but the added resources of Hollywood created more chaos than stability. Cronenberg was doing script rewrites as they were filming, scenes were added and dropped, and, unable to come up with a satisfying conclusion, Cronenberg filmed multiple possible endings. Cronenberg ran out of time and budget, so the filming had to be rushed and Universal took the final cut of the film away from him, putting out a version of Videodrome that compromised Cronenberg’s original vision Nonetheless, Videodrome is an amazing achievement that is so predictive in terms of addiction to media, the rise of virtual reality, and how our understanding of what being a human is has changed through the evolution of technology is more prescient now than when the film came out in 1983.

The themes of the film are an extension of what Cronenberg had explored in his earlier movies but Videodrome is his most intense and complex interrogation of how humanity as become an extension of technology rather than the other way around. Although it can be considered a body horror film with beautifully grotesque hybrids of flesh and machine, it can also be argued that Videodrome is more of a mind horror film because what’s really central in the film is an examination of how control over consciousness and perception will influence how one sees and experiences reality. Cronenberg was reacting to the accusation that violent and sexualized media would cause people to commit violent sexual crimes. Cronenberg shows that human beings influence media just as much as media influences us. Media doesn’t create these dark impulses, but acts like a mirror that may enhance our interest in sex and violence but these urges don’t originate from films, music, television, or videogames. Our instinctual compulsions are part of being a human and the more we deny them the more they can be manipulated and used to control and exploit us. The more reliant we become on technology and media, the easier it is for those who wield power through technology and media to take advantage of our total dependence and misplaced desires. When Max has sex with his pulsating, throbbing TV, he has become totally engulfed by both his human sexual drive and the promise that technology can satisfy and fulfill all our needs and wants.

Perception is reality so if our perception can be directed and dominated then what we see and experience as real can be influenced quite easily. In the film, Brian Oblivion, who has died years ago and has left behind thousands of videotaped lectures, appears to be still alive because he and his daughter totally control the public’s perception of him through the media. We see this same concept on reality tv, where the supposed reality of what happens has actually been orchestrated and manufactured by the producers of the show. Nothing is real unless we see it on a screen. The idea of the Cathode Ray Mission, where homeless people are given access to media as part of the necessities of survival, has become a reality as many approaches to addressing homelessness in the US and Europe involve giving people smart phones and access to places where they can get free Wi-Fi because of the belief that technology has become an essential aspect of living in the 21st century.

There are enough ideas in Videodrome for a hundred movies: the flesh gun that grows out of Max’s hand, the incredibly realistic looking snuff film footage, the plot to use video signals to engineer a fascist social and political order, the idea that a brain tumor isn’t bad but opens up consciousness of a higher reality, the notion of being literally programmed by inserting a video tape into a human body, corporations using broadcasting to modulate and experiment on the masses. Cronenberg is an absolute genius, and this is his first masterpiece. He foresaw the melding of humanity, biology, media, and technology and all the consequences that have entailed over the last forty years. What causes this film and, by proxy, Cronenberg himself, to be so important is that both the film and Cronenberg have a philosophy and that makes Videodrome and Cronenberg not only dangerous but still crucial even forty years later. Long live the old-new flesh