El Salvador: Chronicles of a Country Where Almost Nothing Is Left in Its Place

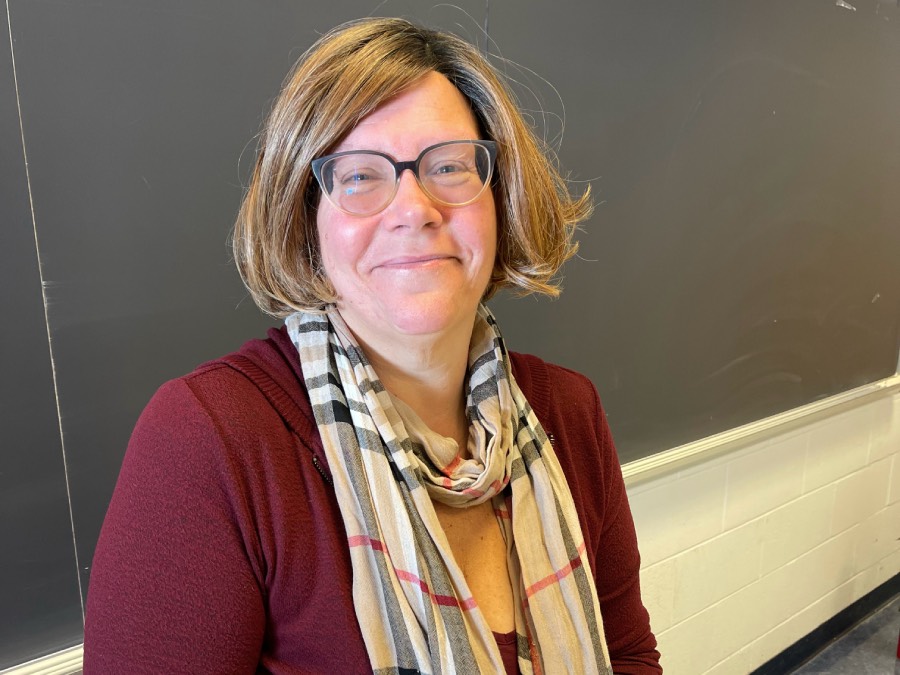

A digital collage portraying the current crackdown in El Salvador. President Nayib Bukele ordered a state of exception on March 27, a day after a high death toll at the hands of gangs.

May 15, 2022

When my uncle was waiting for his preliminary hearing, on March 27 El Salvador woke up under a state of exception in which certain civil liberties guaranteed in the Constitution are suspended. Since then, the streets and neighborhoods of the small Central American country have been patrolled by military and police forces, leaving a chain of tragedies: President Nayib Bukele and the police with more power, the free press under harassment; and my uncle’s arbitrary detention case.

March 26 was the darkest day in the country’s recent history since the end of the civil war. Over 70 people were killed – many of them randomly by gang members. Thus, Bukele, the world’s youngest head of state, ordered his Legislative Assembly, which is made up of the majority of his party, to decree a 30-day regime of exception. Then the crackdown on the Salvadorans began: now we can be detained if the soldiers or the police consider us suspicious of being part of a gang. We can be arrested for 15 days without the right to see a judge, just as our communications can be intercepted without a judge’s order. More than 10,000 suspected gang members were arrested in just a few days, a big number for a small country of 6.5 million population.

Then, on April 6, with reduced freedoms for all, it came the turn for the press: Bukele ordered his assembly to approve the ley mordaza that punishes with between 10 and 15 years in prison any media that reproduces or transmits messages “originated or allegedly originated” by gangs and that could generate “anxiety.” 15 years in a country where rape is punishable by six to ten years.

Six months before the state of exception, on Oct.19, my uncle, a 28-year-old stonemason’s assistant, whose name I will withhold to protect him from possible reprisals, had got up at six-thirty in the morning to go to his job. Then, at four in the afternoon, he returned home where he told my grandmother, “Mami, I will be right back, I’m going to help Kike (affectionate name of another uncle of mine), with the cows, I’m not going to use the motorcycle, I’m going to walk.” However, the night passed and he never returned home.

“He always answers his phone quickly,” my uncle’s girlfriend told me over a phone call, recalling the details of that day. “But that day, when I tried to call him the operator answered, I couldn’t contact him and I stayed up all night worrying, wondering where he was.”

The next day, however, since my family lives in a small town where everyone knows each other, a witness informed my family that after my uncle left a local restaurant, police officers stopped him and told him to put his hands up, then they started hitting him and took him away unconscious in their patrol car. After my family heard about this, they quickly went to the police department of Chalatenango to find out if what the witness was saying was true. Although the delegation did not give them much information, they learned that he was arrested for a large “illicit possession,” and for being a gang member. My family, including myself, were left confused, just wondering why he was accused of being linked to a gang.

When my family arrived home they saw a recent post on Facebook with a photo of my uncle. He was on a hospital bed unconscious with visible signs of beatings. In the same post, there was also a mugshot of another man around the same age as my uncle. The caption read “Gang members arrested with large amounts of drugs.” When my family saw that my uncle had supposedly been arrested together with another person, we questioned, even more, wondering why the witness had not mentioned the other man that supposedly my uncle was arrested with.

On October 25, my uncle had his initial hearing, in which the judge collected all the “evidence” that the prosecution brought to show the judge that they have enough evidence to convict my uncle. In the brief hearing, my family learned the exact charges my uncle was being accused of and what happened when he was arrested. The official police statement says:

“Agents of the National Civil Police were conducting a preventive patrol at 7 p.m., when they suddenly observed that a motorcycle with two passengers made a sharp movement to escape, on noticing police presence. The agents chased them but caught them quickly. The driver of the motorcycle was caught first, then the second one (my uncle) was caught after he fell off a roof he had climbed on, then he was taken to hospital as he was feeling unwell and could no longer walk. The backpack that the driver was carrying was found with a large amount of marijuana in it, for which they are charged for illicit trafficking and for being active members of a gang.”

Although the lawyer spoke to my uncle for 5 minutes and listened to his version: “that what the police said was not true,” he did not give much hope that my uncle would be able to get out of the accusations against him. But my family did not remain with their arms crossed, they had in mind what the witness saw; wondered who was lying, or who was telling the truth.

“This is where our own investigation began,” said my tía Ana, a 32-year-old clothing saleswoman. “We couldn’t just sit with our arms crossed, we felt there was something fishy going on and we needed to do something.”

First, they started with the witness who had told them what had happened to my uncle, but he refused to testify because he was afraid of the authorities. Then they went to the street where my uncle had allegedly been arrested and noticed that a small shop had cameras. My family boldly asked for the video of that Tuesday, and successfully got it. When they saw the tape, they discovered that the man who had supposedly been caught with my uncle, was arrested when he was buying a drink in that shop and he never ran away, and my uncle’s presence was never seen on the tape.

Then, with the help of a social worker, they were able to get my uncle’s medical report from the day he was hospitalized. In short, the report said:

“Patient named… was brought at 7:30 p.m. to the emergency room by police officers who informed the doctors that they were on a routine patrol when they saw the patient in a suspicious attitude, so they tried to intercept him, and he ran away. At the time of the chase, the patient suffered a fall from a roof, with which he lost his consciousness and presented convulsions, and was transferred to the hospital. When the patient was received by the doctors he was unconscious, with foam at the mouth, bilateral nystagmus, and redness in his chest… When the patient recovered consciousness he told the doctors that ‘the police had hit him and wanted to kill him, that they wanted to accuse him of carrying a package that did not belong to him, and that he had not suffered any kind of fall.'”

After gathering all this evidence, my family quickly handed it over to my uncle’s lawyer. When he analyzed the evidence, he saw that everything was distorted, wondering why the police had told a different version of the facts in the hospital. He then concluded that it may perhaps be a case of arbitrary detention.

To argue and present this evidence, they had to wait for my trio’s preliminary hearing scheduled for Feb. 25. But, when the day of the hearing finally arrived, it never took place because it was canceled. Instead, it was rescheduled for April 28, one day after my 21st birthday, and 3 days after the state of exception was extended for another 30 days.

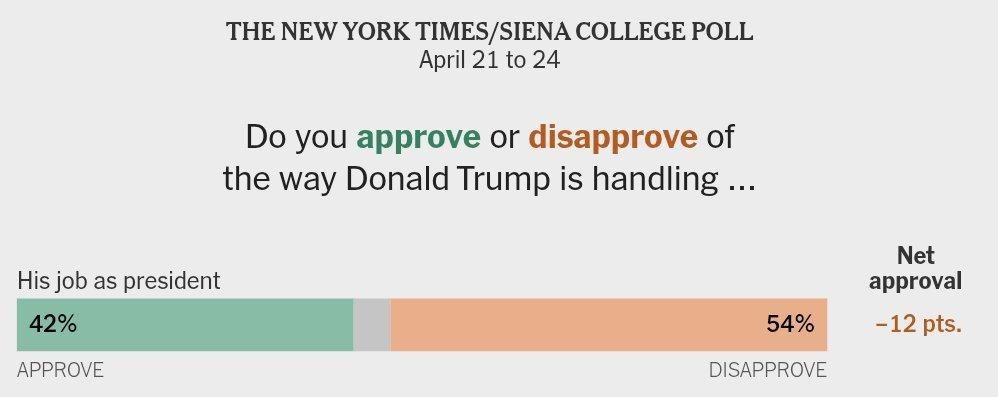

On April 24, following a petition, again by Bukele, the Assembly extended the regime of exception decree for another 30 days. In total, At least 24,000 people have been arrested. All these measures have raised alarm among human rights groups who say it is one of the latest examples of Bukele’s push to rapidly consolidate power.

“All this restriction of rights that has taken place is being justified, or they want to base it on the fight against gangs,” Abraham Abrego, director of the strategic litigation program at Cristosal, a non-governmental organization in El Salvador said. “But in reality, there is an accumulation of power, it is also a restriction, or limitation of rights because what we have seen are mass arrests without warrants, police breaking into homes without warrants. There have been cruel degrading treatment like torture of people by the authorities, something that is not integrated under the regime of exception. This shows abuse of power and a clear practice of human rights violations. Also, those that Bukele’s government considers adversaries or actors who are revealing information that he does not want to be disclosed are targeted. So this makes journalists, and human rights organizations that are recording or filing complaints, targets.”

Although my family and I were worried that my uncle’s hearing would be canceled due to the state of exception, when April 28 arrived, the hearing was not canceled, yet there was no verdict either, only the additional fact that his last hearing is scheduled for June 1, at which the police officer who arrested my uncle will testify, and the evidence given to the lawyer by my family will be shown, as it was not accepted at this recent hearing. Despite this, my family was happy to finally be able to see him, although it was from a long distance. He was also able to meet his two-month-old daughter and scream out

“I love you all so much.”

“He looked like he couldn’t walk, as if someone had hit him,” said my aunt Ana, with watery eyes as we spoke on facetime. “When we arrived at the hearing, the police told us to buy him food because he hadn’t eaten for two days due to the state of exception.”

The future verdict of my uncle’s case as well as of this regime has been left uncertain.

“If they (the government) reach May 27, when the extension expires, and want to continue normalizing this regime,” said Abrego, “It would definitively be breaking the entire framework of the Constitution.”