Louisa Lopez Taitt, 19, was born visually impaired and now attends Suffolk County Community College, studying early childhood.

“The world around that I live in isn’t made for people who are blind,” she says, hoping to spread awareness for the visually impaired community. She imagines it’s much harder to adapt for people who become impaired later in life, but since Lopez Taitt was born visually impaired, learning to adapt was part of her everyday life.

Learning to make cereal was a challenge when she was younger. She would pour her milk before her cereal, and when pouring the milk, she often spilled it. There were devices she could use that would beep when the right amount of milk was poured, but Lopez Taitt didn’t like these devices since she has sensitive ears, so she had to learn to use other senses to make her cereal.

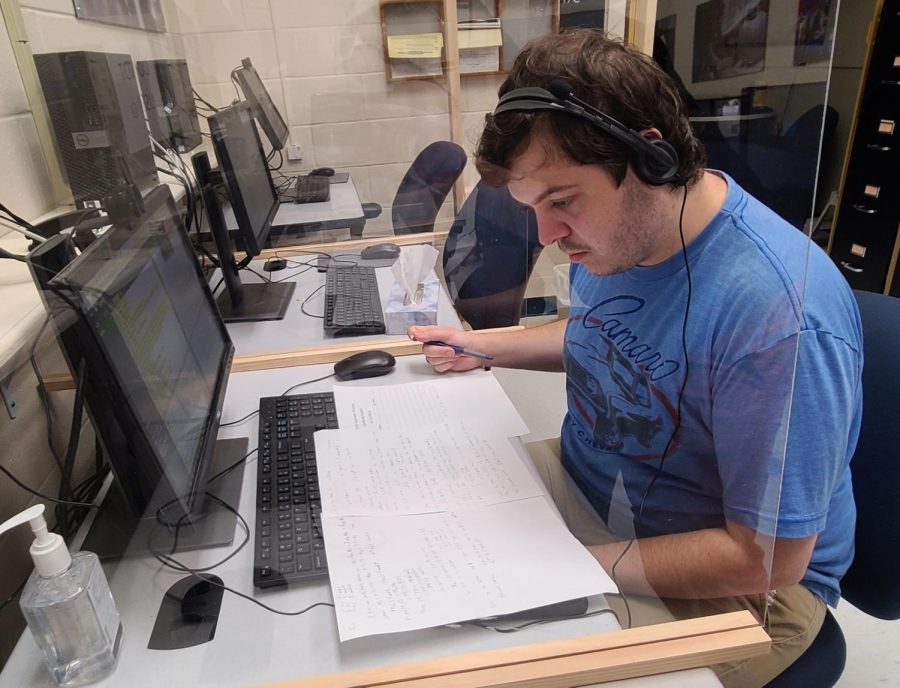

“Some people say I have super hearing,” Lopez Taitt said, having testing accommodations throughout her schooling. She takes her exams in a separate classroom with less distraction because she can hear everything. She has software that reads her exams to her, and all her exams are enlarged.

In grade school, “I felt like the odd one out when your difference in disability context may stand out more.” Lopez Taitt went to South County Public School. She felt emotionally and mentally that getting through school was hard because she couldn’t do everything her peers would do, leading to a lot of her schooling being modified.

Socially, she had peers in class who asked how she was doing in passing conversations, but she didn’t have friends like people usually do. She knew her classmates were going out on weekends, but she would stay home and run errands with her aunt. Since being in Suffolk, she has made friends, “But even then, they have their own friends and I understand that,” Lopez Taitt said.

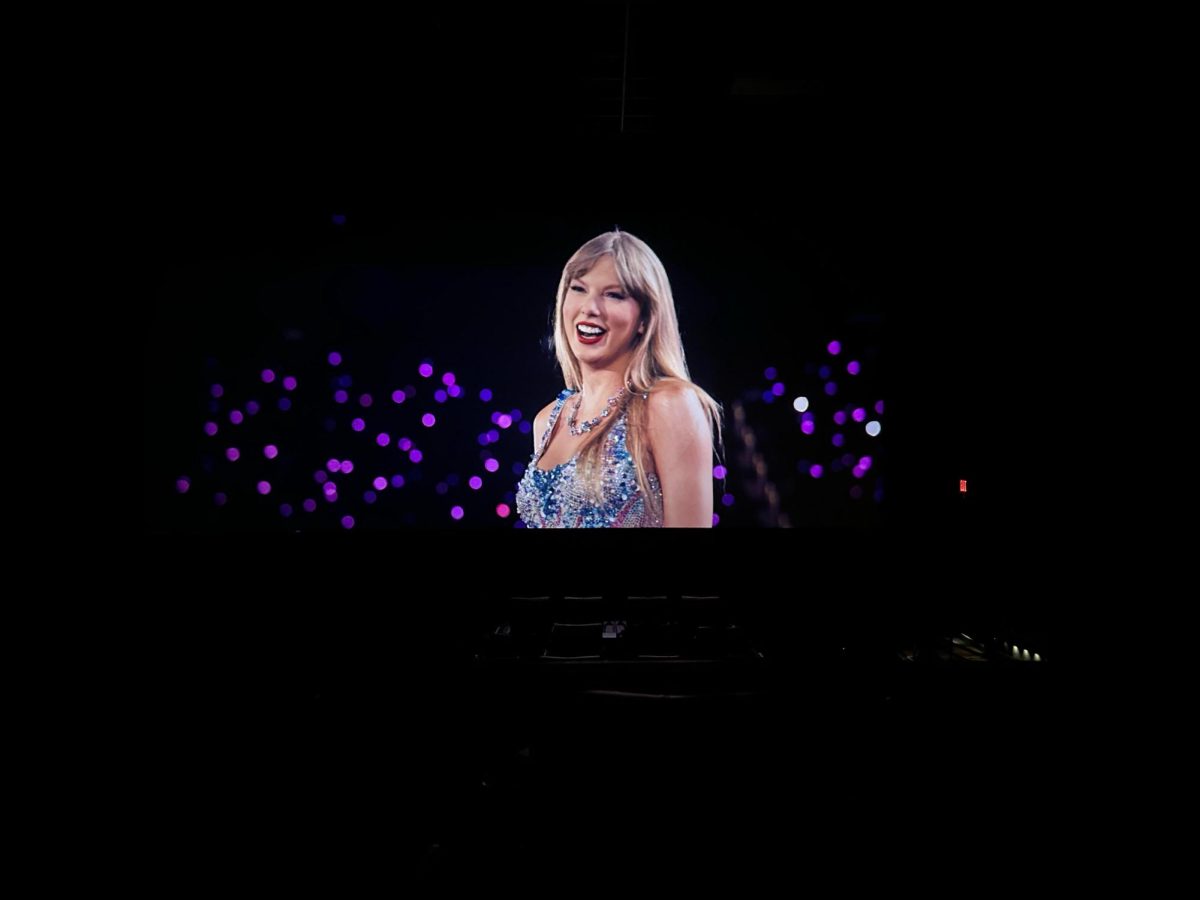

Lopez Taitt was in the school choir and faced many challenges when learning music. “Singing can be a visual thing, especially when learning to read music notes or sight reading, as they call it,” she said. She isn’t the best at sight reading but has learned the basic notes.

Lopez Taitt learned her music for performances with help from her teachers, who gave her CDs with her music on them or the songs on YouTube. Taking a lot of time and effort, she would practice until she memorized everything she needed to know.

Transitioning from high school to the real world came with more complicated challenges. Socializing is still no exception. Most people use body language in conversation, while Lopez Taitt must use her sense of tone. Because she can’t read facial expressions, sometimes she misinterprets what people are trying to say.

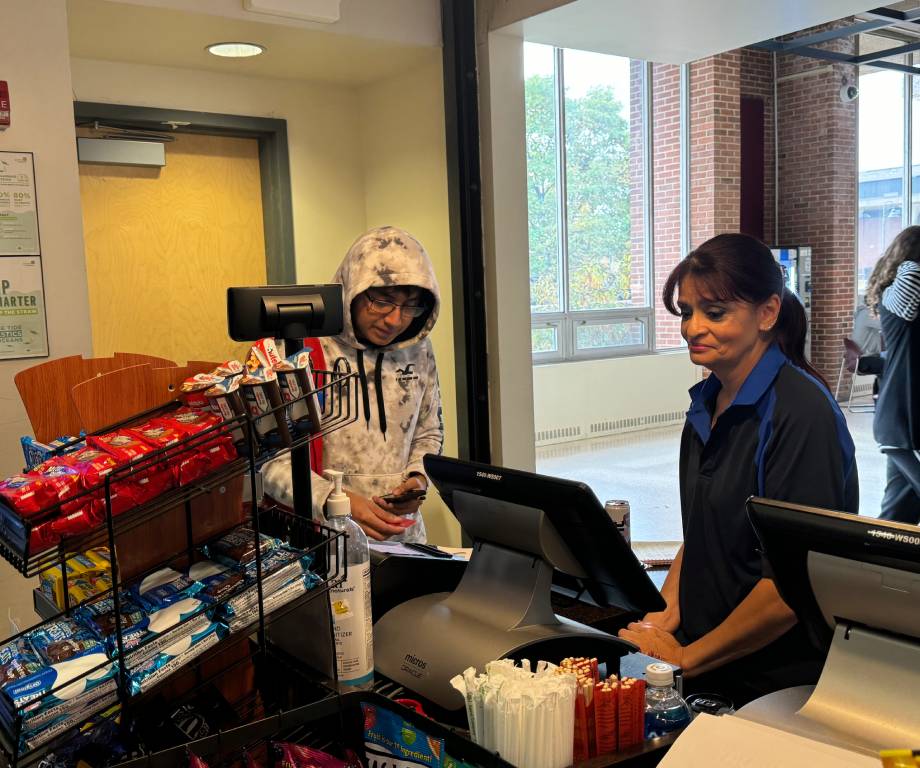

Lopez Taitt takes SCAT, which stands for Suffolk County Accessible Transportation. This is public transportation that transports people with disabilities, whether visible or invisible. The bus fare is four dollars each way, so a whole week of school costs Lopez Taitt $40 in transportation. These buses also don’t always come on time, “My first semester, I had an eight o’clock class, and I had to get up at five a.m. to make sure I made the bus to get here on time, but at the same time, I was also exhausted,” Lopez Taitt said, being on campus her first semester from eight a.m. to four p.m.

“I call it a spectrum,” Lopez Taitt said while explaining visual impairment. “Everyone is different and tools work differently for each person.”

People who are declared legally blind have 22/00, meaning they can stand 20 feet away from the big E, which has a font size of 200, and that is the only thing they can see. People with peripheral vision can see 20 degrees or less from the side. People with low vision have 20/70 vision, meaning they can see the big E and up to size font 70 on the eye chart from 20 feet away. Even someone who is low vision or legally blind will call themselves visually impaired.

She calls it a spectrum because “no one might be exactly the same.”

“I’ve always wanted change,” Lopez Taitt said, feeling things have not been very fair in accommodating her vision loss. “I believe vision loss is the worst of five senses to lose,” she said, saying that vision is the one sense you need to do anything.

Lopez Taitt wants to make it clear, as a person with a disability, that it’s important to remember there is a difference between being rude and asking a question. “If you want to ask about my vision or my vision impairment in general, you can ask without being sarcastic or sticking your hand in people’s faces.”

“I’m not perfect. I try my best, and I think that’s important. But for the classmates or people who have different disabilities, they might have to work ten times harder.”