Ravenous Bloodsucking Monsters Always Wanting More, More, MORE!

February 14, 2022

“It is a joy to be hidden, but a disaster not to be found” — D.W. Winnicott

In the great virtual metaverse that we find ourselves increasingly living in, there is one currency that carries more value than any other. In fact, this exchange is the opposite of the crypto currencies that have become the 21st century equivalent of buying the Brooklyn bridge. The essential online cache is validation from friends, peers, contemporaries, and even strangers. One’s self worth is bolstered by likes, views, retweets, and comments as even negative remarks and trolls have their place in this exchange of self-respect and character for recognition. There’s nothing inherently wrong with desiring acknowledgment; it’s believed that social approval and endorsement are among the most crucial human needs: the necessity to say “I matter,” “I have worth,” “I am important,” and to receive responses to these existential declarations from others who are also seeking to establish their significance. And yet psychologists have identified an obsession with self and of demanding attention from others without reciprocity as characteristics of narcissistic and antisocial personality disorders. Narcissists and psychopaths don’t actually feel anything authentically; their lives are a deceptive charade. Sufferers of these pathologies lack any sense of an inner character and are only focused on the outer appearance and how they look: the physical, the surface, the facade, the material, the exterior, the semblance. Narcissists and psychopaths mimic real emotions in hopes of ensnaring others into glorifying them, as well-meaning people give their time, energy, money, and, most critically, their attention to these con artists.

Can the ability of narcissists and psychopaths to elicit self-aggrandizing authentication from their victims be equated to social media and social networking users’ need to be constantly verified by their audience? Do these attention monsters only feel emotions when they count up views, likes, and thumbs up emoticons? Can they feel happiness, sorrow, or outrage without posting about it and expecting others to give them a disingenuous pat on the back? Do these inner experiences have any worth if they can’t be publicly displayed, viewed, shared, tracked, and commented on? As Facebook/Meta becomes more and more vilified, perhaps the worst aspect of social networking sites is the encouragement of validation addiction, where users need acknowledgment like a drug, a compulsive habitual dependence on the recognition and attention of others.

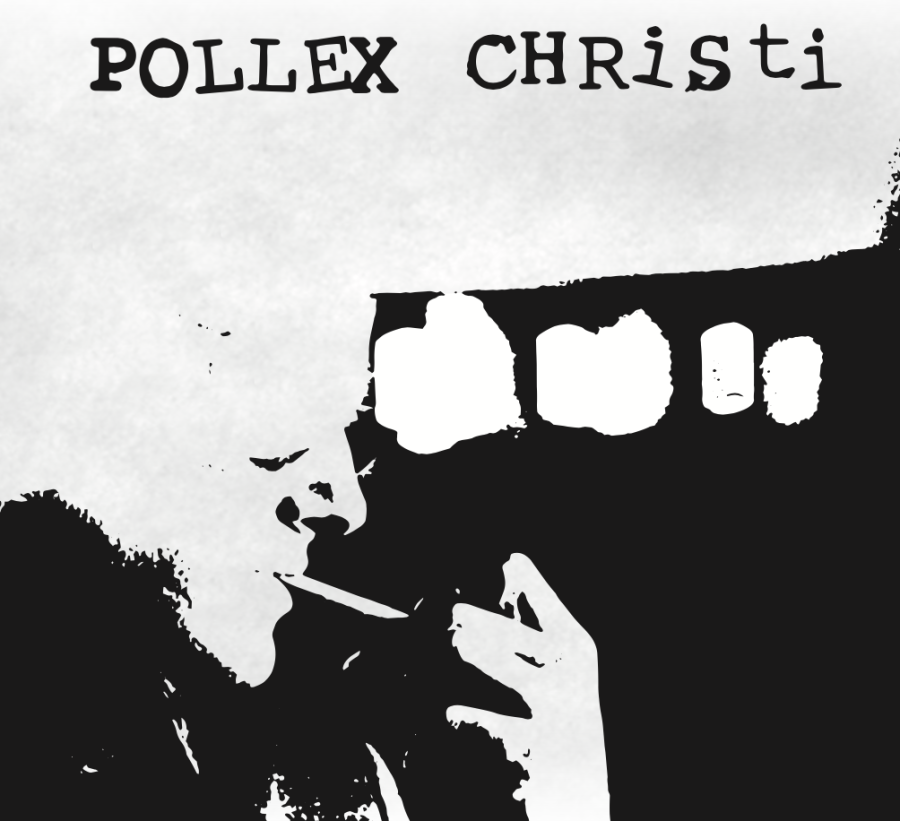

While we now live in a world of “post-digital realism” in which online, information, and virtual technologies are so ubiquitous that it is impossible even to imagine realistic alternatives to them, perhaps there is another way to step away from the kudos devouring spectacle and into genuine situations created by ourselves for ourselves and nobody else. The person who created this “other way” is Nigel Sinatra, but who was better known by his pseudonyms N. Senada and the Mysterious N. Senada. Senada was born on May 28th 1907 in Bavaria, Germany. Little is known about his childhood, and Senada’s name first came to public notice with his 1937 musical composition “Pollex Christi.” “Pollex Christi” (which translates to either “The Big Toe of Christ” or “The Thumb of Christ”) mainly consists of borrowed pieces from other composers’ works such as Beethoven’s “Symphony No. 5” and Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana.” Senada also left large gaps in the score of “Pollex Christi” so that the performers could insert music of their choosing, thus “becoming composers themselves.” “Pollex Christi” was met with critical derision in Germany, with the media calling him a plagiarist, a thief, and a “cultural pagan.” He was ridiculed by critics and smeared by the press. Senada did nothing to deny these accusations, instead responding: “If a man steals philosophy from many great thinkers and combines them into a new philosophy, is he not yet another great thinker?” Senada left Germany in 1938, in response to the scorn of his peers and the growing dominance of the National Socialist movement. He next lived in northern Canada, where he abandoned musical composition altogether, claiming that the music inside him was now “too frightened” to come out. Despite this, he maintained an interest in sound and musical theory, and much of his philosophical work was born from this period.

After the end of World War II, Senada continued travelling, ending up in San Mateo, California in the early 1970’s. It was here that Senada formulated the Theory of Obscurity. The Theory of Obscurity states that artists can only produce the purest expression of their art when the expectations and influences of the outside world are not taken into consideration at all. The artist must not seek any attention, validation, acknowledgment, regard, or ovation. Anonymity prevents artists from receiving any acclaim outside of their own feelings of accomplishment and satisfaction. The public’s opinions, praise, damnation, awards, censure, and/or neglect mean nothing. The artist’s experience is the artist’s experience without the need for refracted glory or approval. Of course, this type of stance flies in the face of not only our collective validation addiction, but also our consumer culture in which we must advertise and sell ourselves every day. To be successful, a product must be identifiable and popular, a highly visible brand that has fans and buyers. Is this not also how social media and social networking obsessives market themselves? The image needs watchers, supporters, and corroborators. In the eye of the spectacle, attention junkies will do anything, no matter how degrading, to stay on other people’s radars.

N. Senada died in a hotel room in Barstow, California in 1993. No media announced his passing, and no one truly knows the extent of his written and musical works because he lived his enigmatic theory. Seemingly, in the 21st century, his theory of obscurity died with him. And yet what would it be like if we tried to practice his cryptic theory on social media and social networking sites? What if we purposely obscured ourselves and stopped offering ourselves to public surveillance? What if we stopped begging for likes, views, comments, and emoticons? What if we stopped commodifying and monetizing our experiences and emotions? What if anonymity truly brings the greatest freedoms? What if we stopped always looking out but started looking in more? Would the silence be deafening? Or would it be the most beautiful music we ever heard?